Darwin inviting Eve to examine the inner workings of the

Darwin inviting Eve to examine the inner workings of the

Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil

Illustration by Julia Suits

Behaviors motivated by our moral sense or advocated by past and present moral codes can be called descriptively moral, meaning described as moral in one culture but perhaps immoral in others. Are some of these behaviors and norms actually universally moral, as our intuitions tell us, or will that question be forever debated? Does being universally moral somehow require a behavior to also be innately obligatory regardless of our needs and preferences, or are universality and being obligatory independent qualities of morality?

This essay answers these questions while proposing the following. 1) All cooperation problems relevant to morality share a common ultimate source in the cooperation/exploitation dilemma: how to sustainably obtain the benefits of cooperation without exploitation destroying future benefits of cooperation. 2) This dilemma implies a universal moral principle. Both the dilemma and its implied universal moral principle are innate to our natural world.

Searching for morality’s ultimate source

Descriptively moral behaviors, such as those motivated by our moral sense and advocated by past and present cultural moral norms, make up much of the data set we can use to test hypotheses about the origin and function of ‘moral’ behavior. Here, ‘moral’ is in quotes because these judgements and norms are contradictory, sometimes strange, and some, such as the more than thousand year old Viking moral norms regarding raiding monasteries and villages, are morally horrifying to modern sensibilities.

Could identifying the ultimate source of these descriptively moral behaviors shed light on what is universally moral?

There has been a growing consensus over the last 50 years or so that descriptively moral behaviors are biologically and culturally selected for by the benefits of cooperation in groups they produce[2,,5,6,11,17,19]. So is evolution the ultimate source of descriptively moral behaviors? Evolution is only the process that biologically encodes certain behaviors in our moral sense and culturally encodes them in moral norms. There is nothing universally moral about evolution’s processes of variation, selection, and replication, or even increasing reproductive fitness, preserving species, or preserving “life”. These processes and these goals can be accomplished by immoral as well as moral means.

Let’s try a higher level of causation.

Could the cooperation strategies that evolution is encoding be morality’s ultimate source? Winning cooperation strategies can include morally despicable exploitation of out-groups. So, again, there is nothing universally moral about cooperation strategies in general and no obvious subset of universally moral behaviors.

But there is arguably one more level of causation. Consider the problem that is solved by these cooperation strategies.

Morality’s ultimate source in the cooperation/exploitation dilemma

In our physical reality, large benefits of cooperation are commonly available. However, initiating cooperation exposes one to exploitation, meaning someone accepting help or goods but not reciprocating either directly or indirectly. Exploitation is almost always the winning strategy in the short term and can be in the longer term. But exploitation and the conflict it produces can make cooperation unsustainable. These circumstances create a universal cooperation/exploitation dilemma. How can species overcome exploitation’s short term “winning” hand in order to sustainably obtain the large benefits of cooperation?

This cooperation/exploitation dilemma must be solved by all beings that form highly cooperative societies.

Fortunately for us, our ancestors chanced upon elements of strategies, including reciprocity strategies and displays of moral virtues, which solved this dilemma. (Moral virtues such as courage, magnanimity, and humility are markers of being a reliable person to cooperate with as well as being elements of strategies to resolve conflict[5]..) Biological evolution encoded these solutions in our moral sense and cultural evolution encoded them in our moral norms.

Our ancestors thus discovered “morality”. Even a flawed understanding of morality has enabled us to become the incredibly successful social species we are.

Reciprocity strategies are perhaps the most effective means found to date for overcoming the cooperation/exploitation dilemma. Game theory shows [1,3,4,15,18] that reciprocity strategies have three necessary elements: motivation to risk initiating cooperation (helping), motivation to punish exploitation or otherwise reducing the benefits of cooperation (though that punishment[11] may be just shaming or shunning), and criteria for when to do both.

Biological evolution’s implementation of reciprocity strategies in our moral sense appears to have specifically encoded: 1) our motivating “helping” emotions[10] compassion, gratitude, and loyalty, 2) our motivating “punishing” emotions[10] contempt, disgust, anger, shame, and guilt, and 3) circumstances that cross-culturally trigger right/wrong moral judgments[9]:: care/harm, fairness/cheating, loyalty/betrayal, authority/subversion, and sanctity/degradation.

Cultural evolution’s implementations of elements of reciprocity strategies in cultural moral codes[8,11] are far more diverse than that in our moral sense’s underlying biology. Nevertheless, we can still identify the three necessary elements. We find 1) advocacy for initiating cooperation, such as “Do to others as you would have them do to you”, “Defending other people and your country is a moral obligation”, and “Do not kill, steal, or lie” (cooperate by not doing these things even when you really want to), 2) advocacy for punishment of moral norm violations such as “an eye for an eye”, enforcing justice as part of rule of law, and shaming those who violate group marker norms such as sexual and food taboos, and 3) definitions of circumstances that trigger cooperation and punishment such as “Has harm been done to someone in one of my in-groups?”, “Is someone disrespecting my in-groups’ markers of morally required hair style, dress, behavior, or sacred beliefs?”, “In time of war, don’t cooperate with enemies”, and “If people break the law, leave punishment beyond shaming and shunning to the law”.

But what about Buddhist “loving kindness” and Christian “forgiveness” rather than “punishment” as the most moral responses to exploitation and harm to others? People are more complex than game theory’s simple agent models. A common goal encoded into our moral sense is to be a member of cooperative groups. Understanding why people act in anti-social ways and, in essence, inviting them back into a cooperative relationship with the group can therefore sometimes be a successful replacement for “punishment” as a component of strategies to overcome the cooperation/exploitation dilemma.

We can explain the existence of all these specific motivating emotions, moral norms, and circumstance triggers as selected for by the benefits of cooperation they produced.

Since this cooperation/exploitation dilemma is innate to our natural world, it reveals the ultimate source of descriptively moral behaviors independent of biology, evolution, game theory, and human thought.

Could it also reveal what is universally moral?

Universally moral ‘means’

There appears to be a subset of strategies that are a necessary part of all strategies that sustainably solve the cooperation/exploitation dilemma. Even strategies that exploit or war against out-groups[17] must begin by cooperating in an in-group[7]. In order to maintain sustainable cooperation in the in-group, others within that in-group are not exploited.

Thus we have a behavior that is necessary to all descriptively moral behaviors: “Solve the cooperation/exploitation dilemma without exploiting others”. Since it is necessary to all descriptively moral behaviors, it is universally moral among human moral behaviors.

For example, direct and indirect reciprocity strategies that exploit no one are universally moral. And as already referred to, displays of ‘pagan’ virtues such as courage, magnanimity, and leadership, and ‘Christian’ virtues of humility, meekness, quietude, asceticism, and obedience can solve cooperation problems both by being markers of reliable cooperators and improving conflict resolution[5]. Thus, display of moral virtues can also overcome the cooperation/exploitation dilemma without exploiting anyone and are universally moral.

Culture specific implementations of these strategies will commonly differ in the strategies emphasized, definitions of in-groups where cooperation is focused and out-groups with less intense cooperation, markers of membership in both, heuristics for advocating initiating cooperation and punishing exploiters, and the moral virtues that are emphasized. It is the strategies themselves that are universally moral, not their implementations in different cultures.

Also, note this is a definition of moral ‘means’ (moral actions), not moral ‘ends’. Aside from a vague goal of “overcome the cooperation/exploitation dilemma”, this principle is silent about moral ends. But could a definition of only moral means be the basis of culturally useful moral codes? Consider that versions of the Golden Rule, moral heuristics favored around the world, are effective moral guides with no stated end or purpose. Kantianism’s categorical imperatives are examples from traditional moral philosophy of other moral principles that also only define moral means. The lack of a stated end for morality does not prohibit a culturally useful moral code.

Why might a society prefer to advocate and enforce an evolutionary morality based on this universal moral principle above all others? While science cannot tell us what we ought to do in an ultimate sense, science can inform us how we are most likely to fulfill our needs and preferences. Societies could decide to advocate for and enforce such an evolutionary morality because they expect many of their needs and preferences can be best met by increasing cooperation in their societies consistent with this universal moral principle:

First, the principle advocates increased cooperation which directly increases material benefits and, perhaps more importantly, increases emotional rewards triggered by cooperation, particularly cooperation with family and friends.

Second, cooperation strategies are innately harmonious with our moral sense and emotionally motivating since our moral sense was selected for by cooperation strategy benefits.

Also, this moral principle is an objective reference for resolving disputes about morality because its definition is a product of objective science.

Would most of us prefer to be guided by some traditional moral code or philosophy with mysterious burdensome obligations or an evolutionary morality devoted to increasing the benefits of cooperation? Further, what secular goal might we prefer for a moral code except increasing the benefits of living in our society, and what other moral principle is universally moral as a matter of science?

In addition, it can be culturally useful to better understand what is merely descriptively moral and not universally moral. For example, once a food or a sexual behavior avoidance has become common for whatever reasons, food and sex taboos can become merely markers of membership[13,14] in an in-group. Religious people in particular may still feel strongly that such moral norms must remain part of their personal morality, but intellectually knowing that these are in a sense arbitrary should encourage consensus on not including them in public morality enforced by the society as a whole.

Also, it could be useful to understand that moral norms such as “Do to others as you would have them do to you” and “Do not kill, steal, or lie” are not universally moral when acting on them would decrease the benefits of cooperation (and thus not solve the cooperation/exploitation dilemma). Intellectually understanding these are only fallible heuristics by, again, religious people in particular could increase consensus about when and how to enforce them as part of public morality. For example, this understanding could increase consensus regarding abortion, euthanasia, and morality in time of war when the Golden Rule is abandoned.

On its own, “Solve the cooperation/exploitation dilemma without exploiting others” is not a useful moral guide for daily life. People need something more specific. “Increase the benefits of cooperation without exploiting others” may be slightly more useful. “Increase the benefits of cooperation by doing to others as you would have them do to you” advocates initiating indirect reciprocity by a reassuringly familiar moral guide with a twist that makes it universally moral.

As mentioned, responding to immoral behavior with “loving kindness” and forgiveness rather than shaming, shunning or more severe punishment may sometimes be more likely to actually “increase the benefits of cooperation” (be moral). Knowing when “loving kindness” and forgiveness is the most moral action when dealing with others, as well as when dealing with our own personal failings, is a subject ripe for study.

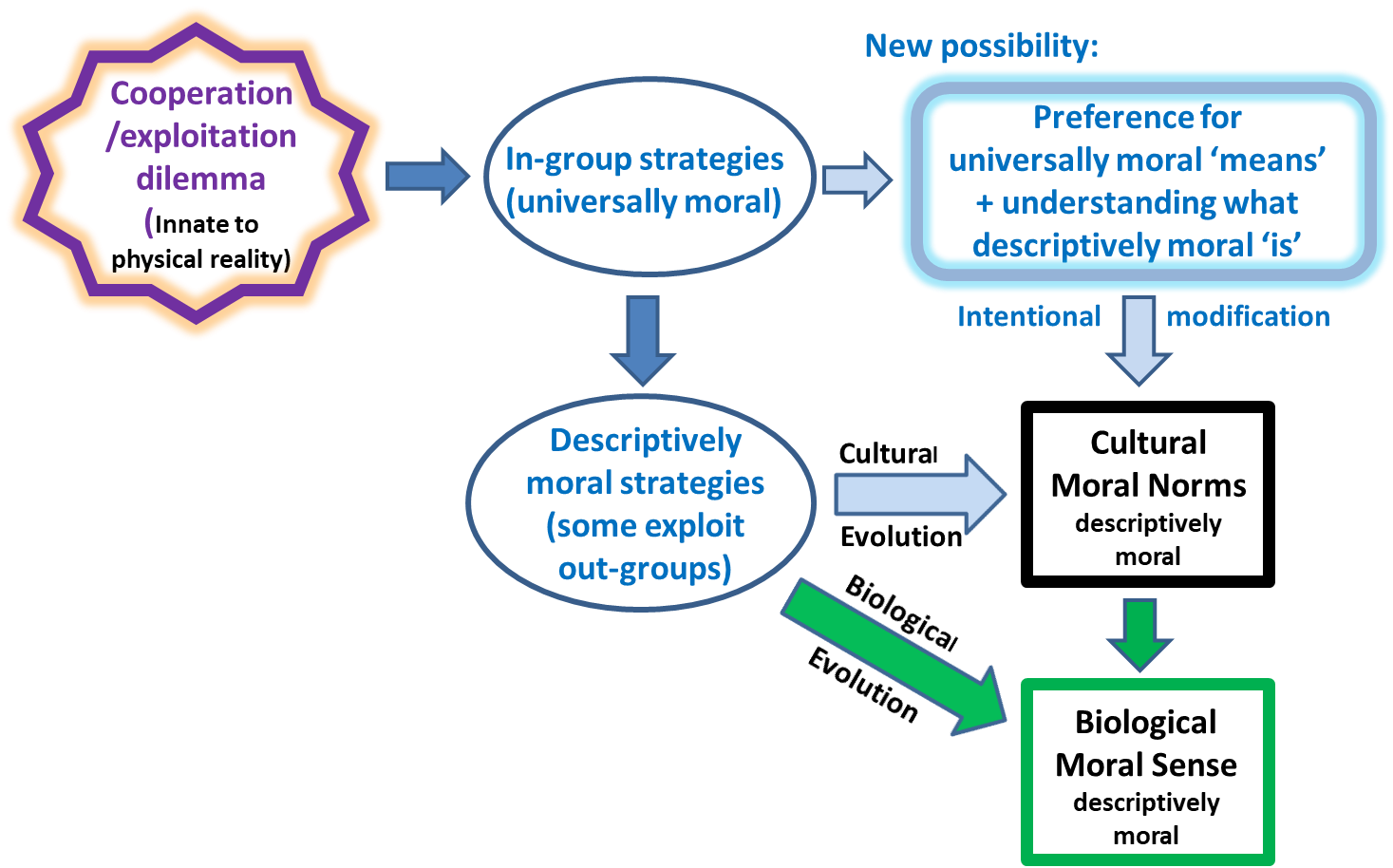

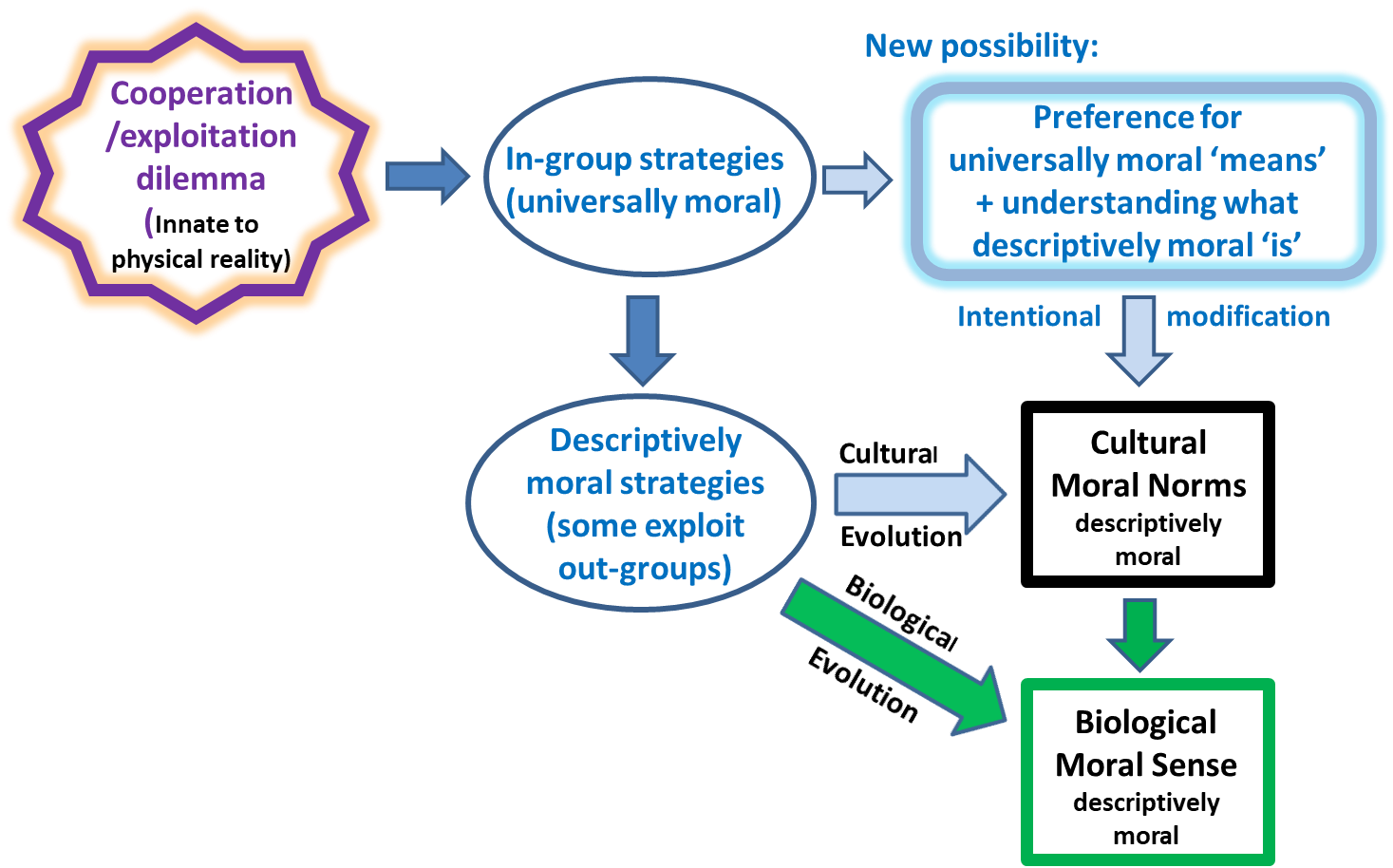

The components of morality as solutions to the cooperation/exploitation dilemma can be conceptually understood as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Morality in science: innate, mathematical, intellectual, and observed

Figure 1. Morality in science: innate, mathematical, intellectual, and observed

Objections to this universal moral principle

Couldn’t kin selection solve this dilemma as appears to be the case for social insects that also form highly cooperative societies? What part does kin selection have in moral universals?

What separates moral norms from other cultural norms is the common feeling (and practice) that violators deserve punishment[11]. Punishment of violators is a necessary component of all reciprocity strategies. However, kin selection (also called kin altruism) such as altruistically helping and caring for our children can be evolutionarily stable (a winning strategy) without any ‘violator’ punishment component. Kin selection has a different relationship to human morality than reciprocity strategies and the moral virtues described above.

You say this moral principle from science is not innately binding. Then what makes it “moral”? And in any case, aren’t you committing the naturalistic fallacy?

This principle is “moral” because it is a necessary component of all solutions to the cooperation/exploitation dilemma relevant to human morality, meaning relevant to our moral sense and cultural moral codes.

Objections to a morality’s lack of innate bindingness arise from the natural feeling produced by our moral sense that our moral judgements are strangely binding and obligatory regardless of our needs and preferences. Why do people feel this way?

People naturally feel “that there is an objective higher code to which we are all subject” because our ancestors who felt like this were better cooperators[16]. Our predecessors whose neurobiology did not trigger bindingness feelings for moral norms tended to act more selfishly, obtained fewer benefits of cooperation, and mostly died out. Natural variation, selection, and replication produced this well-known, but too often still mysterious, illusion of bindingness. The common illusion that what is moral must be innately binding provides no rational basis for rejecting the proposed moral universal.

Innate bindingness and universality are independent qualities of this moral principle. The former is an illusion; the latter is real.

The “naturalistic fallacy” when referring to the is-ought problem is the fallacy that we can derive an ‘ought’ only from what ‘is’, perhaps from what ‘is’ natural or the product of evolutionary processes[20]. Since the proposed universal moral principle makes no claim for innate bindingness (what we somehow ‘ought’ to do), it does not commit the naturalistic fallacy.

Aren’t there philosophical arguments against the existence of moral universals?

Some philosophers have objected to the idea of a universal morality based on the diversity, contradictions, and strangeness of the elements and qualities of human morality. John L. Mackie proposed that the best explanation of these puzzling observations is that these merely “reflect adherence to and participation in different ways of life”[12] which suggests that there are unlikely to be facts about what is universally moral.

As already described, science can now explain 1) the observed variations in moral views, 2) our “intractable” opinions about morality and why morality’s quality of bindingness is so strange, and 3) specifically when and why our “special faculty of moral perception or intuition” triggers moral judgements. Mackie’s objections have been answered by science.

Would moral philosophers who accept this proposed moral principle’s universality be out of a job?

No, this universal principle does not supersede moral philosophy; it provides a new grounding for moral philosophy. The bare claim is “strategies that overcome the cooperation/exploitation dilemma while exploiting no one are universally moral”. A tremendous amount of philosophical work would be required for this principle to become culturally useful. This work might be particularly productive for increasing human flourishing due to 1) its grounding in science, 2) its core function of increasing the benefits of cooperation, and 3) its innate harmony with our moral sense. Some needed study areas are listed below. Items 4) through 11) may be largely unexplored philosophical ground.

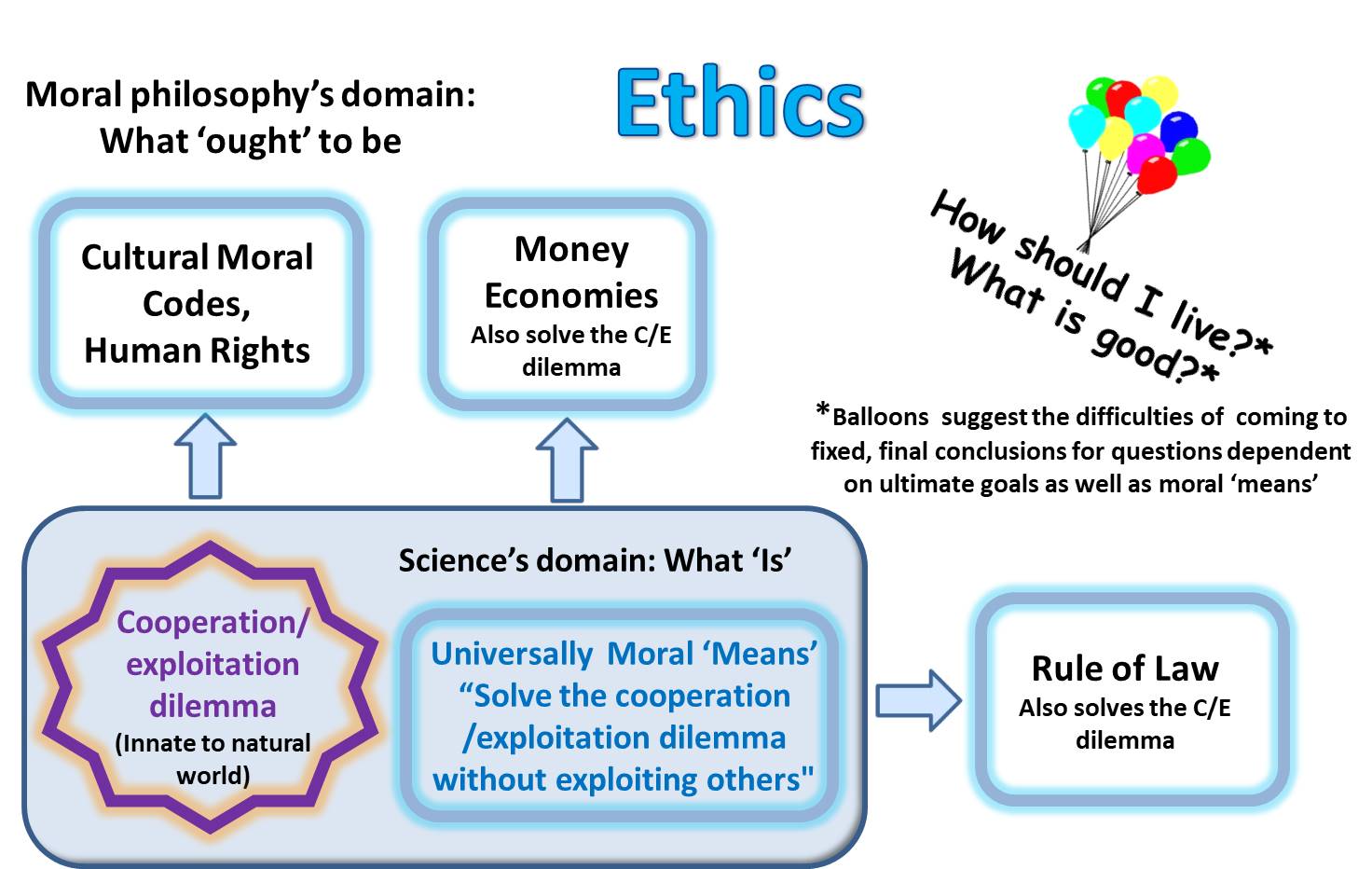

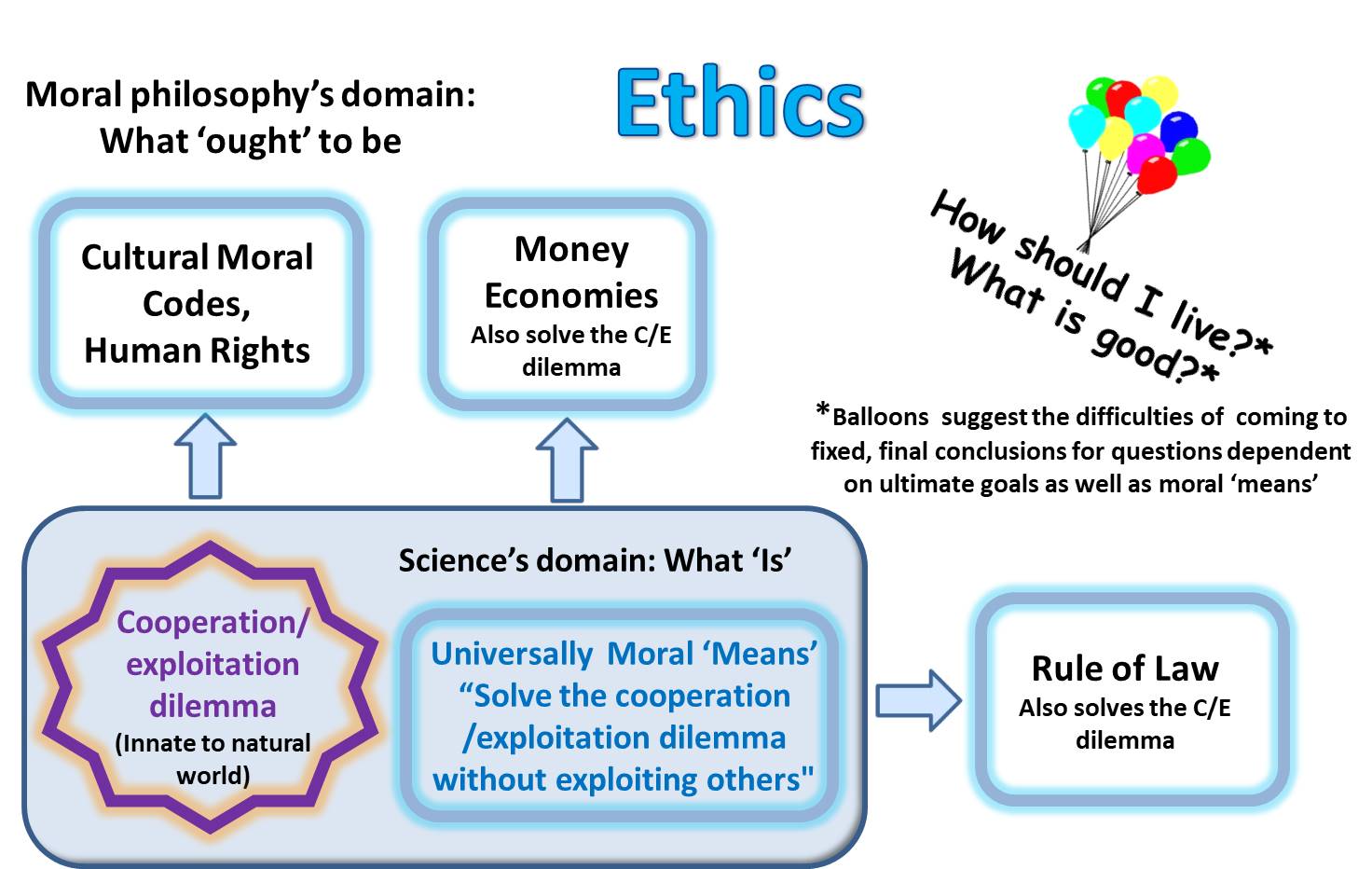

Philosophical work would still be needed to 1) propose who ought to be included in “others” who are not to be exploited, 2) justify goals (which science is silent about) for the cooperation those strategies enable, 3) propose what our moral obligations are to care for animals and ecosystems, 4) clarify how to coherently apply this moral principle to interactions between groups and within hierarchies, 5) clarify what is morally admirable, merely moral, immoral, and morally neutral, 6) translate the cooperation/exploitation dilemma versions of “cooperation” and “exploitation” into human moral terms, 7) integrate this universal moral principle into existing philosophical moral systems, such as utilitarianism (it defines moral ‘means’ for utilitarianism’s moral ‘ends’) and virtue ethics (it defines virtuous interactions with other people), 8) investigate implications for human rights and justice as fairness, 9) investigate implications for the morality of other solutions to the cooperation/exploitation dilemma such as money economies and rule of law, 10) use all this knowledge to suggest refinements to cultural moral norms in societies with different histories and in different environments, and 11) suggest when inevitable moral norm contradictions due to different applications of the strategies are best just tolerated.

Also, this universal moral principle illuminates only the subdomain of “ethics” that covers moral means for interacting with other potential cooperators. This universal principle is not sufficient to answer larger philosophical questions which may be dependent on ultimate goals such as “How should I live?” and “What is good?”

Figure 2 illustrates science’s universally moral ‘means’ as a new foundation for ethics. Note that money economies and rule of law are also solutions to the cooperation/exploitation dilemma. Their morality can be judged by the universal moral principle in the same way cultural moral norms can be judged.

Figure 2 A new foundation for ethics

Figure 2 A new foundation for ethics

References:

- Axelrod, R. (1984). The Evolution of Cooperation. New York: Basic Books.

- Bowles, S., Gintis, H. (2011). A Cooperative Species: Human Reciprocity and Its Evolution. Princeton University Press.

- Boyd, R., Richerson, P. (1992). Punishment Allows the Evolution of Cooperation (or Anything Else) in Sizable Groups, Ethology and Sociobiology, 13:171-195. DOI: 10.1016/0162-3095(92)90032-Y

- Boyd, R., Gintis, H., and Bowles, S. (2010). Coordinated punishment of defectors sustains cooperation and can proliferate when rare, Science, 328, 617-620,

- Curry, O. S. (2007). The conflict-resolution theory of virtue. In W. P. Sinnott-Armstrong (Ed.), Moral Psychology (Vol. I, pp. 251-261). Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- Curry, O. S. (2016). Morality as Cooperation: A problem-centred approach. In T. K. Shackelford & R. D. Hansen (Eds.), The Evolution of Morality. Springer.

- Fu, F., et al. (2012). Evolution of in-group favoritism. Scientific Reports 2, Article number: 460. doi:10.1038/srep00460

- Gavrilets, S., Richerson, P. J. (2017). Collective action and the evolution of social norm internalization. PNAS vol. 114, no. 23

- Graham, Jesse, Haidt, J., et al. (2012). Moral Foundations Theory: The Pragmatic Validity of Moral Pluralism. Available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=2184440

- Haidt, J. (2003). The moral emotions. In R. J. Davidson, K. R. Scherer, & H. H. Goldsmith (Eds.), Handbook of affective sciences. Oxford: Oxford University Press. (pp. 852-870).

- Harms, W., Skyrms, B. (2010) Evolution of Moral Norms. In Oxford Handbook on the Philosophy of Biology ed. Michael Ruse. Oxford University Press

- Joyce, R. “Mackie’s Arguments for the Moral Error Theory” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, <https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/moral-anti-realism/moral-error-theory.html>

- McElreath, R., Boyd, R., Richerson, P. (2003). Shared Norms and the Evolution of Ethnic Markers. Current Anthropology, Vol. 44, No. 1. pp. 122-130

- Meyer-Rochow, V. B., (2009) Food taboos: their origins and purposes. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 5:18 https://ethnobiomed.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1746-4269-5-18

- Nowak, M. A. (2006). Five Rules for the Evolution of Cooperation. Science, 314(5805), 1560-1563. doi: 10.1126/science.1133755

- Ruse, M., & Wilson, E. (1985). The evolution of morality. New Scientist, Oct 17, 1478.

- Tooby, J., and Cosmides, L. (2010). Groups in Mind: The Coalitional Roots of War and Morality, from Human Morality & Sociality: Evolutionary & Comparative Perspectives, Henrik Høgh-Olesen (Ed.), Palgrave MacMillan, New York, pp. 91-234.

- Trivers, R. L. (1971). The evolution of reciprocal altruism. Quarterly Review of Biology, 46(1), 35-57. doi: 10.1086/406755

- Tomasello, M., & Vaish, A. (2013). Origins of Human Cooperation and Morality. Annual Review of Psychology, 64(1), 231-255. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143812

- Wilson, D. S., Dietrich, E., Clark, A. B. (2003). On the inappropriate use of the naturalistic fallacy in evolutionary psychology. Biology and Philosophy, 18(5), 669–681.

Darwin inviting Eve to examine the inner workings of the

Darwin inviting Eve to examine the inner workings of the Figure 1. Morality in science: innate, mathematical, intellectual, and observed

Figure 1. Morality in science: innate, mathematical, intellectual, and observed Figure 2 A new foundation for ethics

Figure 2 A new foundation for ethics